Scilly’s Entrance Graves

The Isles of Scilly is an ancient tapestry of towering granite, woven across thousands of years to become the archipelago we know and love today. The chambered tombs known as ‘entrance graves’ are a magnet for visitors and islanders alike. From the spectacular circular mounds of Upper Innisidgen and Porth Hellick Down to the secretive grave tucked away on Samson’s south hill, they command attention and intrigue wherever you go.

Scilly’s entrance graves are not entirely unique to the islands but are referred to as Scillonian simply because their numbers are not rivaled anywhere else. It’s likely they originated here but it’s difficult to know for sure as similar sites can be observed in west Cornwall. It’s the ever familiar mystery of who did it first? What makes Scillonian entrance graves different comes down to two main factors: smaller workforces and a unique environment. Less people to build them means they are far smaller than the ones in, for example, Brittany. And building an entrance grave on a remote island in Scilly is going to be a completely different experience than building it in Ireland or Devon, anyway.

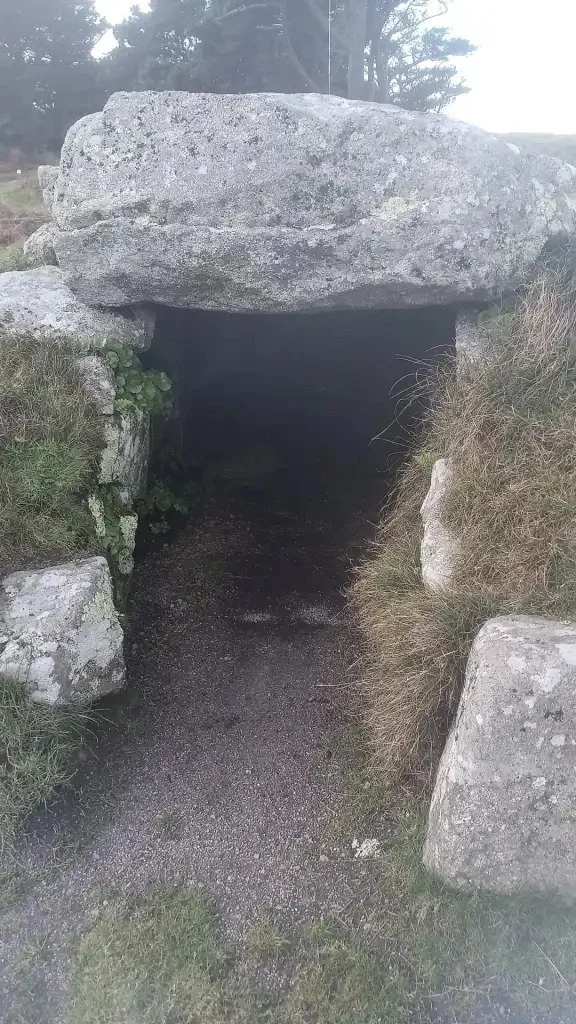

Scilly Entrance Grave ©Simon Nicholls

Inside the Entrance Grave ©Simon Nicholls

It’s suggested the practice of burying the dead in communal tombs continued on Scilly longer than other locations across Europe. Scilly has always been a bit behind the times, even in the Bronze Age. These graves may have had other uses — marking boundaries between families, used for rituals and ceremonies, or acting as landmarks. They would have once been located inland, surrounded by fields and farmland, and are noted to appear often in groups of three.

Another factor that makes these graves unique to Scilly is the mystery of the directions in which they face. On the mainland many chambered tombs like these often face the midsummer sun, but on Scilly they face entirely random directions. No one is sure what the significance behind this may be. It’s clear the early Scillonians didn’t do things aimlessly; when you’re hauling giant pieces of rock, little is done without reason.

In Celtic mythology, burial mounds were believed to be entrances to the Otherworld, a parallel realm hidden under the ground or beneath the surface of the sea. The description of them being ‘entrance’ graves is curious considering the countless myths involving doorways and portals surrounding places of the dead. Of course, the term derives from the way the chambers were easily and regularly opened for new burials, and to leave items inside as one might leave flowers on a grave.

Scilly has an interesting connection to Greek mythology with the archipelago’s nicknames being ‘The Fortunate Isles’ and ‘Isles of the Blessed.’ The islands are truly a melting pot of legend. It was believed kings from distant lands were brought here to be buried, but the contents of the graves upon excavation suggest only islanders were buried inside them. Scillonian Bronze Age pottery is incredibly thick and poorly made due to the quality of the materials available, and there’s no evidence of pots made elsewhere being left behind. Perhaps the myth that important individuals were buried here comes from Scilly’s link to the Fortunate Isles of Greek legend, a place where the mightiest heroes go after death. Perhaps they saw Scilly as a gateway to paradise, an Elysium in the mortal world?

The Eastern Isles carry interesting evidence of early occupation, littered with Bronze Age cairns and a Roman period shrine on Nornour. Around this time Scilly would have seen a rise in migrants and newcomers. Scilly has always been a place of travellers due to its position in the Celtic Sea and has a long history of welcoming strangers onto its shores. These islands are a place of change — a once solitary, windswept landmass transformed into a sub-tropical archipelago, prehistoric farmland traded for thriving marine flora and fauna as the sea level rose and divided the islands. The entrance graves are a reminder of Scilly’s long and unique history and its ability to survive the worst of storms, remaining a special and individual place even thousands of years into the future.

Written by Sophie W.